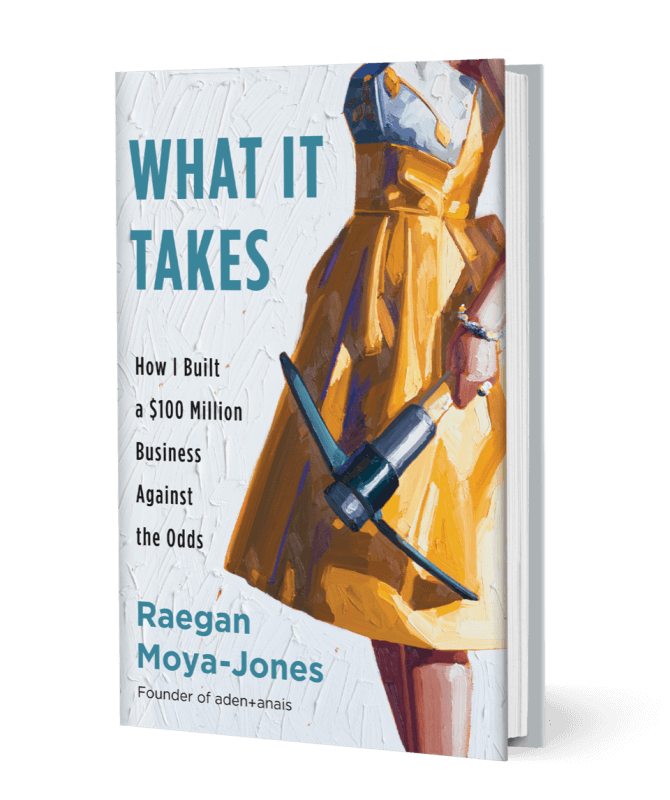

I was sitting on the floor of my friend’s nursery in Los Angeles when the idea came to me.

“Claudia, we need to go into the muslin wrap business!” I said. “And we should call it ‘Aden and Anais,’ after the babies!”

It was May 2004, and I was holding my infant daughter Anais, who was swaddled in a sheet of gauzy muslin. A second muslin blanket was stretched out on the floor; it was “tummy time” for my friend Claudia’s newborn son, Aden.

Claudia was one of my closest friends. When my husband, Markos, and I moved to New York in 1997, we knew no one. Actually, Markos knew one person: the ex-girlfriend of his best friend. Awkward. But Claudia and I hit it off the moment we met and became good friends; she even lived with us for a time. When she met her husband she settled in California and we remained close despite the distance. I was a bridesmaid in her wedding and, should the worst happen, a legal guardian to her children. Because we were Australian, we both knew about swaddling, but had struggled to find swaddling blankets for our babies stateside.

Muslin swaddling blankets—“wraps,” as we called them back home—had been a parenting staple in Australia for as long as I could remember. In fact, for Aussie mums-to-be they’re as essential as nappies (that’s diapers if you’re American). We used them as burp cloths and nursing covers and stroller shades, as changing pad covers and security blankets, and, obviously, to swaddle our babies. One of the great things about muslin—which is really just a gauzy, open weave cloth, a fabric that’s been around since biblical times—is that it’s lightweight and breathable. When used for swaddling, it keeps babies warm while reducing the risk of overheating. It also gets softer with time, rather than falling apart after a few dozen washings.

So I was pretty much blown away when I started shopping for baby gear during my first pregnancy, and I couldn’t find a single muslin blanket anywhere in the United States. I asked shopkeepers at trendy boutiques and chain stores alike, and they all looked at me like I was crazy. I tried searching online and still found nothing. Eventually I phoned my sister Paige, also a new mum, and had her ship over some of the Aussie stuff, which is what Claudia and I were using that morning in L.A. Without even trying, I’d identified a gaping hole in the market. I knew that if Americans were introduced to the product, they’d soon find it as indispensable as we did. Going into business just seemed sort of . . . obvious.

Well, it seemed obvious to me at least.

Claudia, on the other hand, wasn’t so sure at first. “Maybe we should just reach out to one of the Australian companies instead?” she suggested. “Maybe we could become a distributor in the States?”

She had a point. Certainly, it would be easier to become a distributor for an existing brand than to make and manufacture a product ourselves. But as I looked again at her son on the floor and at my daughter in my arms, I thought: How hard can this really be? We weren’t talking about much more than a large square of cotton cloth. And besides, the Aussie wraps I’d grown up with were boring, predominantly white, and sold in cellophane packaging. I knew I could make them beautiful. I could design them with vibrant colors and patterns. I could take white cotton muslin and turn it into something people coveted.

It was not the first idea for a business that had popped into my head. I’d had loads of them over the years, in fact, and I can tell you that not one of them had anything to do with babies. I didn’t have a burning desire to make a product for mums. I didn’t have a burning desire to make a product at all. My motivation was to be the master of my own destiny, to work for myself rather than “the man.” The baby blanket idea just happened to be the first that, upon further inspection, seemed viable. The more I thought about it, the better and better it sounded: Here was a practical product for a proven market that I could actually improve. Better still, the potential for growth—blankets! clothes! sleep sacks! bibs!—was exponential.

The thought of improving swaddling blankets was intriguing, but it was more than that—I knew it was an industry-changing idea. The swaddling blanket would be a unique product in the multibillion-dollar baby industry. It would solve a problem for mothers and create a completely new market segment in the US. I felt within every bone in my body that—finally—this was a great idea to pursue.

It didn’t take much convincing to get Claudia on board—she saw the hole in the market as much as I did. It was just a matter of agreeing on the right way forward. What’s more, while we had our big idea, we still had much to learn. I figured that first on the to-do list was signing up a manufacturer. I thought (naively) that I’d be able to find one somewhere in New York (the garment district was less than two miles from my apartment, after all) or at least somewhere within the lower forty-eight states. So, in my spare time, I started doing research. I made calls. I asked around.

At first, this was not an all-consuming project. I was already busy balancing the demands of my full-time job at The Economist with my responsibilities as a new mum. I wasn’t in much of a hurry to get to market, but no matter how many calls I made or how much research I did, it felt as if I wasn’t making any progress—at all.

This was incredibly frustrating. Muslin was available everywhere in Australia, in the usual boring prints and colors, with its typical stiff feel, so I couldn’t figure out why I couldn’t find it anywhere in the US. Every time I visited a store, the salesperson had to ask me what muslin was. In retrospect, I think part of the reason there was such a hole in the American market was that the very few individuals who knew what muslin was thought of it in its true, raw form: scratchy and stiff, almost like cardboard. They couldn’t easily make the connection between a cheap workhorse fabric and a luxurious, extra-soft baby blanket.

Another part of the problem, I would soon discover, was the collapse of the textile industry in the US. A flood of cheap foreign imports and the growing strength of the dollar—along with advances in technology and the higher cost for domestic labor (compared to foreign labor)—had driven pretty much everybody to use offshore mills just a few years before I started my search. Further complicating matters was the fact that none of the few remaining manufacturers seemed to have any idea what I wanted or, to my total surprise, even understood what I was talking about.

Before long, I resorted to cutting up pieces of my Aussie muslin. Whenever I found a potential manufacturer, I’d send or show the sample to them: This! This is what I mean! Can you produce this fabric? None of them could.

Actually, a few of them could, but only at a ridiculous price point.

Think: $150 and up. For a four-pack of muslin baby blankets.

Over the next nine months or so, my enthusiasm waxed and waned; for a few weeks here and there I’d be laser focused and looking for leads, but then I’d get busy with work and my daughter and not think about the business at all for a while. I had a lot on my plate, as any new mum knows. I was being pulled in multiple directions and living the reality that there are only twenty-four hours in a day. But I truly believed in the idea of aden + anais so I gave it all of the little free time that I had.

One morning I went into work and struck up a conversation with Brenda, our receptionist at The Economist. Somewhere between talk of our kids and bitching about work, the mail carrier came around to drop a huge stack of letters, magazines, and packages on her desk. Right on top of the pile was an issue of Women’s Wear Daily. Since I love a sample sale and a five-inch heel as much as the next woman, I asked Brenda if I could borrow it. As I was flipping through the magazine, I came upon a full-page ad for an Asian manufacturing textile show happening in New York just three days later.

I couldn’t think of a reason not to go. I figured I might as well take my sample of Aussie muslin over there and check it out.

There must have been fifty vendors in that showroom, each of them milling around in their little booths. I started going up to them one by one and asking the same question I’d been asking for a solid year now—“Can you produce this fabric?”—but the answer was always a version of what I had already heard:

No.

I don’t know what that is.

We can’t make that.

After a half hour or so, I was discouraged. After an hour, I was ready to head home. The entire exercise had been such a waste of time that I almost didn’t bother approaching the man in the very last booth by the exit. But I decided to show him the muslin just for the hell of it. His name was David Chen. Like the other vendors, he wasn’t familiar with the fabric. Unlike the others, however, he offered to take the sample back to the factory he worked for to take a closer look.

It would turn out to be one of many serendipitous moments in the history of aden + anais. Because two weeks later, Chen emailed me with good news. For the first time, the answer was yes.

Claudia and I were in business.

We still had a long way to go. Finding a manufacturing partner at that textile show in New York had been lucky, but we weren’t ready to launch a real business yet. My goal from the beginning had never been to simply replicate the Aussie muslin products. What that muslin lacked was softness and beautiful design that would make people want it. I wanted to make it better, so the manufacturer and I set about making the fabric softer by upping the thread count and pre-washing the blankets. He was a creative, persistent partner who was willing to work with me and engage in a lot of back and forth to get the product right—mainly, him sending me samples of muslin and me promptly returning them to China with lots of feedback on how to improve them.

Ultimately, it took us more than a year to get the quality of our muslin where I wanted it, above the quality and softness of the blankets I could find in Australia, but it was worth it. I knew our little company would live or die based in no small part on quality. If we had a chance in hell of succeeding, the product we brought to market had to be perfect.